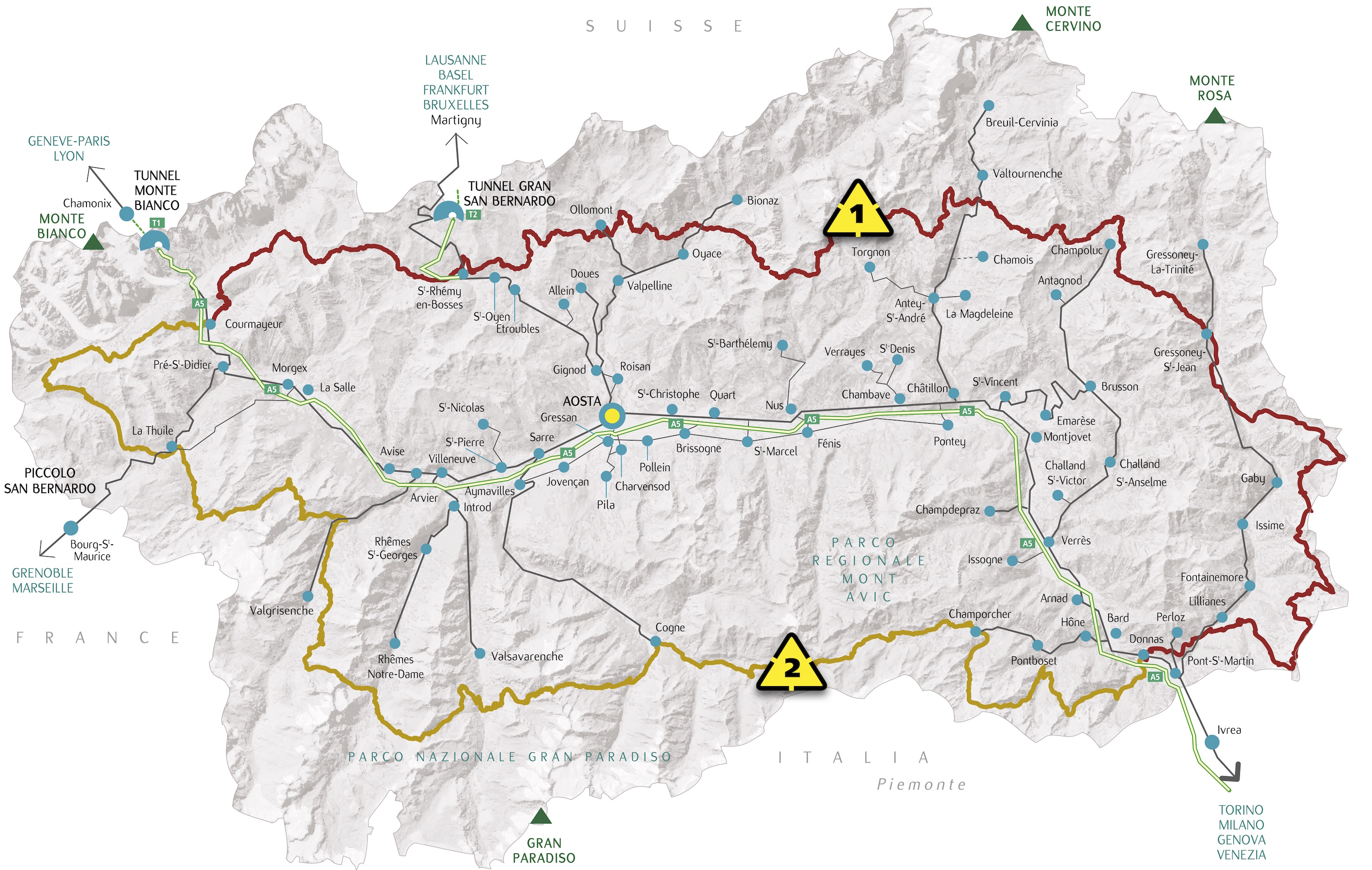

The interesting Roman town of Aosta should be visited along with other remnants of the past such as the Roman bridge of Pont Saint Martin or the numerous chapels that dot the mountainsides. As with many other regions of Italy, there is an exceptional mix of both cultural and natural beauty. Thanks in part to conservation efforts by its long-time rulers a good portion of the Aosta Valley is now protected parkland. The vastest of these is the Gran Paradiso National Park, which is managed together with the adjoining Vanoise National Park in France. Formerly the Savoia’s favorite hunting spot, Gran Paradiso is still today a magnificent mountain wilderness.

For walkers there are innumerable opportunities to explore the park, from simple day hikes to long distance treks. Hike to a mountain refuge at the foot of a glacier, spy families of ibex, chamois and marmots, or pass a former royal hunting lodge. Contemplate, solemnly, the great Gran Paradiso itself, the only 4,000-meter peak entirely within Italian soil. This sublime massif would not be out of place in a less wilderness-challenged continent like North America, with its noble white crown, its proud glaciers and tiny blue-green lakes tucked on its slopes. The Gran Paradiso is the destination of many a mountaineer and trekker; the national park that takes its name is no less worthy of a thorough reconnoiter.

History – The Royal House of Savoy

The Savoia dynasty ruled Italy from 1861 until the establishment of the Italian Republic in 1946, but historically their interests were not centered over the heart of the peninsula. Rather, the center of their extensive pre-Italy domain was great arc of the Western Alps, the current French-Italian border. From 1032 on, in fact, the mountainous terrain of the Aosta Valley was an integral part of the Savoia State. Today this most northwest of Italian regions bears witness to this long heritage, with many strategic castles visible throughout.

The Savoia made their fortune controlling the alpine passes in their territory, and the castles facilitated the collection of tolls as well as protected the route from bandits. The fortifications proved formidable against warring adversaries: the only interlude of foreign rule over nine centuries was that of Napoleon in the early 1800s, and even he had to resort to trickery to conquer the region. The Corsican feared the impregnable Bard castle, so he decided to sneak past it during the night with his troops – and on his return from successful battle in the plains razed the ancient fortress to the ground.

But strategic positions and warfare are not the first things that come to mind upon entering the Aosta Valley from the Piedmont plains. Rather, as a mountain wonderland encloses travelers, one realizes that here there is more than enough stunning material to satiate the senses. High, glacier and snow-covered peaks with narrow valleys leading up to them, each of these in turn aching to be explored with who knows how many lovely alpine lakes, villages, or huts to be found there.

The pre-Italy Savoia realm extended from Lake Geneva in the north to the Mediterranean Sea at Nice, from the Rhone River in the west to the beginning of the Po plains. In essence, the whole of the Western Alps was under their wing, including the control of some of the Alps’ most important alpine passes. Yet the Savoia’s prime location was to be the cause of much of their trouble over the centuries: from the mid-15th century on the alpine state had to deal with increasingly overbearing, heavyweight neighbors, in particular France and the Empire. To keep both at bay required skilled diplomacy, and in many cases successful warfare – often the Savoia State was the first target at the outbreak of a European war. The Savoia counts-dukes-kings thus had their share of difficulties over the centuries. While some rulers handled things more adeptly than others, in the end it was enough to keep their domain intact down to mid-19th century, at which time, thanks to the astute Count Cavour, the mountain realm managed to unite the entire Italian peninsula under its sovereignty.

A rather telling story arises from the unification process: in order to appease their ally Louis Napoleon of France, who was to help the Savoia kick the Austrians out of Italy, the Savoia had to cede their lands west of the alpine divide to France. The soon-to-be king of Italy agreed but stipulated that a certain favorite hunting area over the divide would remain his. Apparently, giving up what had been his ancestor’s homeland for eight centuries did not much concern him (as it infuriated Garibaldi, who felt betrayed upon learning that his hometown Nice had been handed to the French) as much as losing a small mountainous hunting domain. And yet this is clearly within the personality of the Savoia, who, if they may be attributed with one common trait over their entire nine hundred year rule, were passionate hunters. The great hunting residences surrounding their capital Turin, the mountain lodges still visible today in the Gran Paradiso National Park attest to the fact that the Savoia were in thoroughly love with the hunt.

The ibex was one undoubtedly their favorite prey. A magnificent long-horned animal, the ibex has a most astounding ability to climb, far surpassing that of humans. It can in fact rest with ease in places where even the most expert rock-climbing man would have difficulty. Its origins in Italy stem back to the last Ice Age, when it was a plains animal; warmer temperatures forced the ibex into the Alps, where they have remained to the present day notwithstanding near extinction in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Realizing that continued hunting would eliminate their beloved animal, in 1821 the Savoia banned its hunting in Gran Paradiso, for all except the royal family. King Victor Emanuel II in 1856 established stable borders for his royal hunting demesne – and his conservation efforts worked, as ibex numbers rose from 300 in 1850 to more than 2000 in 1878. The disasters of the First World War once again threatened the population: after the war it was King Victor Emanuel III who in 1922 established Italy’s first national park from his former hunting domain of the Gran Paradiso. By the end of the Second World War the ibex, which historically had been present throughout Europe’s mountains, remained only in the Gran Paradiso National Park. Over the last few years the Gran Paradiso ibex has thrived, its population now exceeding 6,000. Furthermore park animals have been used to repopulate other mountain parks throughout Europe. With the establishment of the adjoining Vanoise National Park in France in 1963 and official twin status with Gran Paradiso set in 1972, there are now some 123,000 hectares of contiguous protected wilderness, a fine habitat range not just for ibex and chamois but also the royal eagle.

Wildlife is not the only thing protected in the Gran Paradiso Park. It is a land rich with forests, rivers and lakes, virgin peaks and glaciers – unscrupulous industrial or tourist development would permanently damage the territory, ruining it not just for wildlife but also responsible human enjoyment. In addition, a human cultural aspect of the park is also preserved: former grazing huts and mining camps are preserved alongside royal hunting lodges. With over 50% of the region completely unproductive and with the severe climatic conditions, one can imagine the difficulty natives had in merely surviving from year to year. Only with the recent rise in tourism have park natives begun to see any significant improvement in their lot.

There is then a great deal of both natural and cultural beauty to discover in Gran Paradiso. Ironic perhaps that it was the obsessive hunting personality of the Savoia that began the process of its conservation, but in the end it has been the collaboration of environmentalists, Italian government and local authorities to preserve and help revitalize the region.

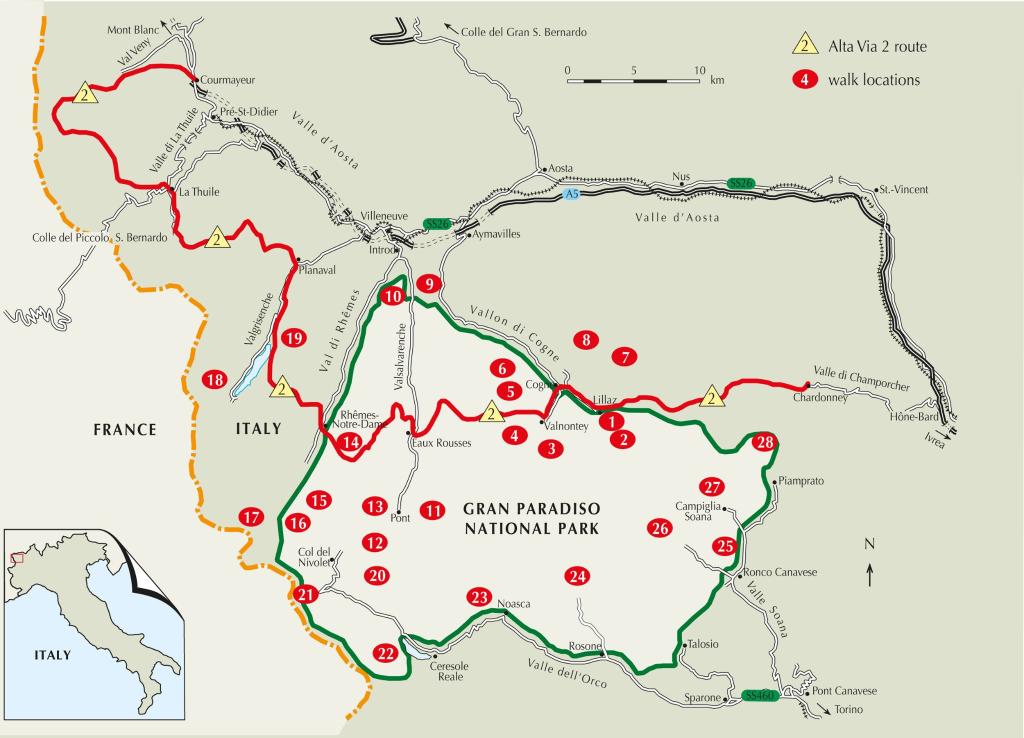

Hiking in Gran Paradiso

In the Gran Paradiso there is walking for everyone, from young school children to experienced trekkers. For the former, one highly recommended outing would be to the old grazing huts above Valnontey, just up the valley from the former mining town of Cogne. Today Cogne and Valnontey have successfully switched to a tourism-based economy, with many fine inns and restaurants located here. At Valnontey in particular there is an excellent restaurant in the central piazza, where polenta alla valdostana (polenta with fontina) and chamois beef are served among other specialties.

For the hike, begin walking in the lovely green basin of Cogne, toward the village of Valnontey. The Gran Paradiso and other peaks loom spectacularly ahead; one is inspired up the switchbacks from Valnontey on the trail toward Rifugio Vittorio Sella. Still below but approaching treeline, after about forty minutes of switchbacks, turn off the trail to the refuge by taking a left over an old bridge.

Up the other side brings one to a large meadow where there are the ruins of several former grazing huts known as the Casolari de la Toule. This is also prime grazing territory for ibex and chamois – come in the spring to see possibly numerous groups of animals. Be sure to keep your distance, particularly with the more sensitive chamois, as the short warm season is the only time these animals can gain nourishment for the long winter ahead. Continually running away from human voyeurs costs them too much energy. It is worth keeping a low profile also for other reasons – to better observe the animals in their customary interaction – the playful ramming of the young males is particularly suggestive.

After a picnic lunch, head back down to Valnontey from the Casolari to conclude this easy half-day walk. For those who wish to walk a full day’s route, or perhaps stay overnight in a mountain refuge, Rifugio Vittorio Sella is an optimal location. Again on prime ibex terrain (though the animals here are quite accustomed to humans by now), here one may also dine well on local specialties – as at other mountain refuges throughout Italy, the cuisine is not lacking. Moreover, here one may experience true “rifugio spirit“: i.e., the fun social atmosphere that arises when lots of active people are together in the same isolated place. On nice days the extensive lawn in front of the refuge turns into a veritable beach, with everyone including the ibex relaxing and sunning themselves.

Aside from the few grand refuges that attract scores during the short summer period, the great majority of the park remains mostly unvisited even during the warm months; and outside of summer the park is more or less deserted save for occasional skiers. Hikers looking to avoid the hut masses have many options, ranging from single day to weeklong, even cross-border excursions into the Vanoise. One superb itinerary entails an early start from Valnontey. Continue up to Rifugio Sella then head south toward the Colle del Herbetet. Below this col is rustic Bivouac Leonessa where one can stay overnight (bring food), dramatically positioned directly beneath the white dome of the Gran Paradiso.

The following day, after a short but intense climb to the Colle del Herbetet, enjoy a long, marvelous descent into the Valsavaranche, one of the most beautiful of the entire park. The Savoia must have thought so too, for one of their (in particular Victor Emanuel II’s) favorite hunting lodges, Orvieille, is located up the other side of the valley. Note that this descent is difficult in places and could very well be covered in snow near the top. Take care, bring a good map and don’t do this alone – overall though the descent from the glacier into the majestic, narrow forested valley is a fantastic one, well worth the effort. The local marmots, cute park sentinels, will cheer you on with their shrill whistles (actually warning their neighbors of your approach). The main Col Lauson route from Rifugio Sella may be a bit easier than the Colle del Herbetet, but the latter is more interesting for its remoteness and the spectacular descent into Valsavaranche. Both require hikers to be in excellent physical condition and to have good previous mountain experience.

Once in the Valsavarenche, relax overnight at the lovely agriturismo at Bien or at one of the other small inns nearby (there is bus service in the valley). The following day one has a myriad of possibilities to choose from – hike up to Orvieille, continue to the next valley to the west, the Rhêmes Valley, or head south to Rifugio Savoia and into France.

For more information on lodging in Gran Paradiso National Park and surrounding areas please contact the Aosta tourist office at +39 0165 236627 or visit their website.

By D. Leibowitz